18th Century in the Russian history

Russia in the 18th century is dominated by two greats, both of whom lived in the 18th century: firstly Peter who created a naval power, modernised the country in the European style and established an empire with a new capital looking west, and secondly Catherine who continued Peter’s reforms and widened the empire’s borders at the expense of Poland and the Ottoman Empire. Uniquely in Russian history, for a large part of the 17th century the country was ruled by female leaders.

Beginnings of the Great Northern War

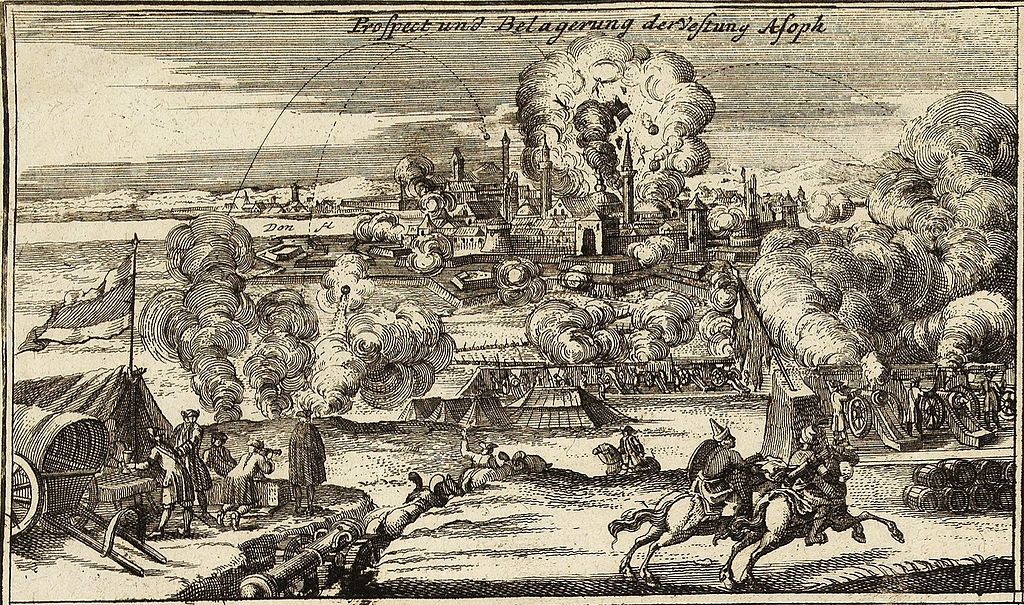

Tsar Peter the Great was not content with the access to the Black Sea he had won with the capture of Azov from the Ottoman Empire, he also wanted access to the Baltic Sea, which was blocked by the Swedish provinces of Karelia, Ingermanland (Ingria), Estland (Estonia) and Livland (Livonia/Latvia). Peter entered into an alliance with Denmark –Norway and Saxony and in 1700 invaded Sweden, laying siege to Narva. However, the Swedish proved too strong and Russia was defeated at the Battle of Narva in 1700. Sweden then turned its attention to Poland, whose king at the time was also elector of Saxony. Peter the Great used this opportunity to attack Ingria once more in 1703 with greater success. The Russians recaptured the Oreshek Fortress in 1702, the Swedish fortress of Nyenschantz, which guarded the mouth of the River Neva, in 1703 and Narva in 1704. King Charles XII of Sweden did have more success in Poland where he managed to have his candidate elected king in 1704.

Battle of Lesnaya

In 1707 King Charles XII of Sweden invaded Russia from Sweden hoping to capture Moscow. However, the harsh winter and Peter’s appliance of the scorch earth tactics put an end to this plan and the army headed to Ukraine to recover. This plan was hampered in September 1708 when the Russians captured Swedish supplies and reinforcements at the Battle of Lesnaya in modern-day Belarus. In October 1708 Hetman Ivan Mazepa requested more troops from Russia to defend his Hetmanate, and when Peter the Great refused, Mazepa and a group of loyal men rebelled and switched sides to the Swedish, annoyed by what he saw as a snub by Russia after the Cossacks had fought in Peter’s wars in the Baltic.

Battle of Poltava

In 1709 the Swedish and Russian armies met in battle in Poltava in modern-day Ukraine were Russia won a decisive battle. King Charles and his ally Hetman Mazepa only just managed to escape the battlefield to Turkey. The Battle of Poltava turned the tide of the war to the benefit of Russia. In June 1710 the siege of Vyborg ended with the Swedish surrender and in 1710 the Swedish provinces of Estland and Livland surrendered. Less success was had during the subsequent River Pruth Campaign against the Ottoman Empire which was fought in Moldova. In 1711 the Russian army was surrounded by the Ottomans and Peter had no option but to sue for peace. The resulting Treaty of the Pruth forced Russia to give up Azov and demolish other fortresses in the surrounding area.

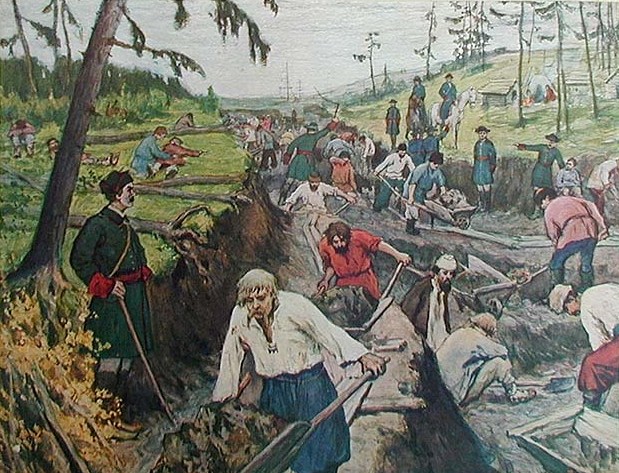

Window to Europe

Back in 1703, Peter ordered the construction of a new fortress on an island on the mouth of the River Neva, close to the site of the old Swedish fortress of Nyenschantz. The fortress was named the Peter and Paul Fortress and the city of St Petersburg was thereby founded while the Great Northern War was still raging in the surrounding area. Tens of thousands of peasants were conscripted to build the new city, which included the draining of swamps. The hard work and unforgiving climate claimed the lives of many. To speed up the construction process, Peter banned all other stone construction work in the empire. In 1712 the new city was decreed to be the capital of Russia and Peter ordered that noble families move there and build palaces on the embankments. Due to its location with easy access to Europe, the foundation of St Petersburg is often described as Peter opening (or even beating through) a window to Europe.

Tsar-Reformer

Peter the Great has gone down in history as a tsar-reformer who modernised and westernised Russia. His first reforms were connected with military matters; overhauling the system of recruitment and of course creating a Russian fleet. This, in turn, led to industrial reforms to supply the army and navy, education reforms to teach Russians the required skills of mathematics, science and navigation and wide-scale construction projects, including the first, unsuccessful, attempt to build a canal between the Volga and the Don.

Administrative Reforms

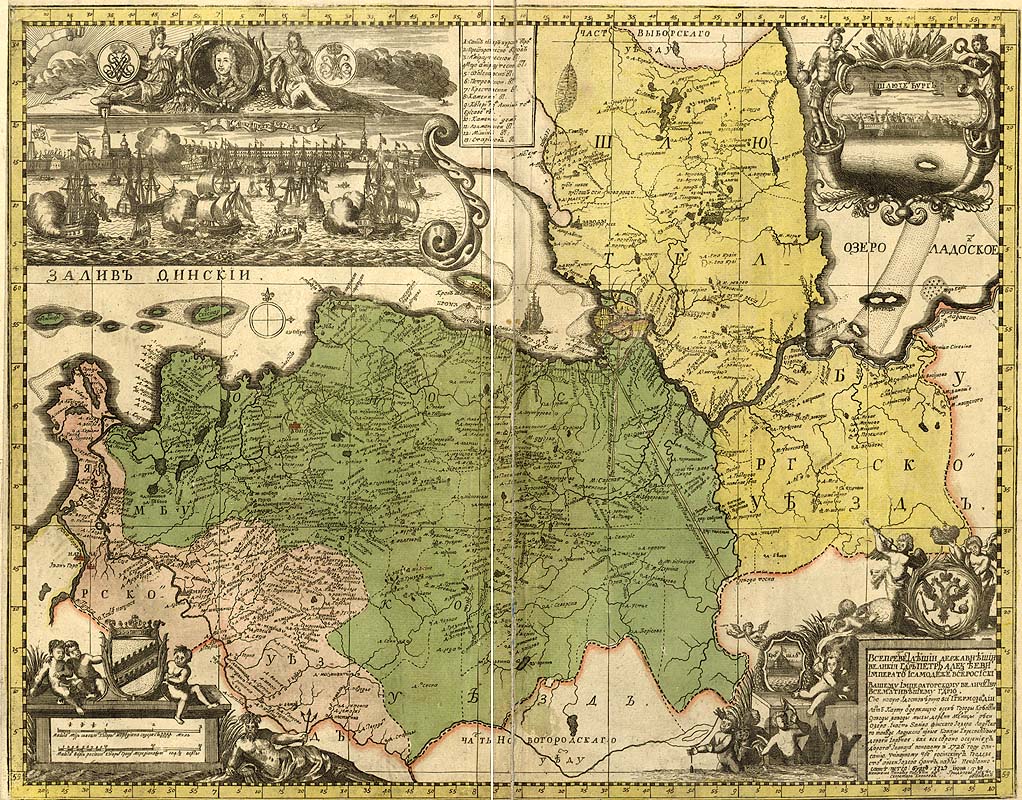

Peter also wished to improve the system of state administration. In 1708 an edict was passed which divided the country into eight governorates: Moscow, Ingermanland with it centre in Shlisselburg (later renamed the St Petersburg Governorate), Kiev, Smolensk, Arkhangelsk, Kazan, Azov and Siberian with its centre in Tobolsk. Each governorate had its own governor and was further divided into districts. In later years more governorates were created.

In 1722 in an attempt to break the heredity system of the boyar nobility Peter introduced the Table of Ranks which created three types of service (military, civil and court) each divided into 14 ranks. Depending on a person’s service he could move up the ranks, regardless of his birth (although this system did not apply to serfs). Back in 1711 Peter permanently established a government body known as the Senate to rule the country while the tsar was on campaign. In 1721 the Boyar Duma was officially disbanded and its functions were transferred to the Senate. The former government department known as Prikazi were also replaced from 1717 onwards with organs known as collegia, later renamed ministries in the 19th century.

Religious Reforms

The running of the Orthodox Church even was even included within the remit of Peter’s Reforms. In 1700 Patriarch Adrian died. Peter had had a difficult relationship with Adrian who often criticised the tsar’s plans for modernisation, especially Peter’s decision to divorce his wife in 1698 and his stance on shaving beards off – which went against Orthodox teaching. Therefore Peter was in no hurry to appoint a successor to Adrian and the position remained vacant. Peter instead established in 1721 a council known as the Holy Synod which would perform the functions of the patriarch. He also put restrictions on young men joining monasteries and thereby escaping their military duties. Peter’s stance in relation to the church even led to some fanatics believing him to be the Anti-Christ, this view was especially shared by the Old Believers.

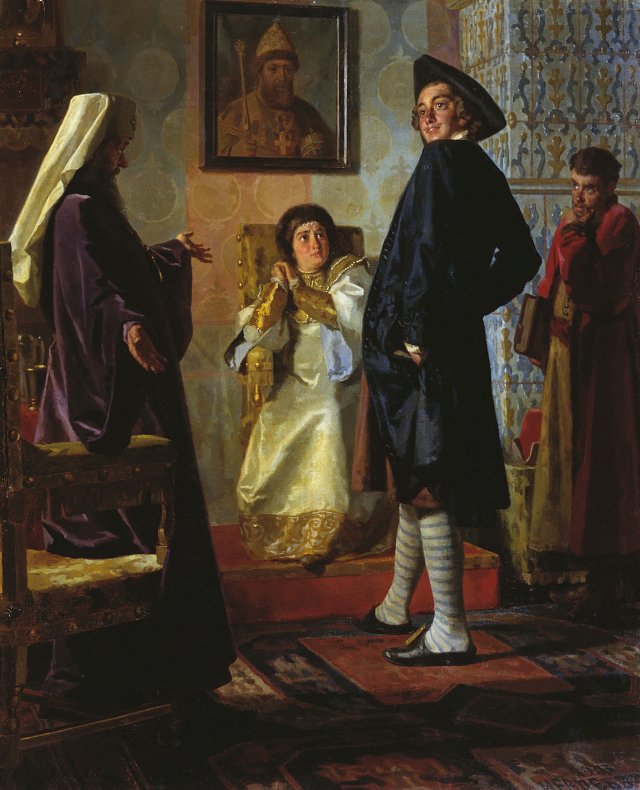

Tsarevich Aleksey

Peter had never enjoyed a good relationship with his son from his first marriage Aleksey. From childhood, Aleksey was brought up by his mother who had a great deal of disdain for her husband. The subsequent divorce of his parents and his mother’s removal to a convent in Suzdal made matters worse. Upon his father’s orders, Aleksey had to serve in the army and he was married off to a German bride whom he did not like. The unhappy marriage did, however, produce two children. Aleksey did not share his father’s views for modernising Russia and adopting Russia traditions, which made him a potential ally to those who shared his views. Aleksey made several threats to become a monk in order to escape his overbearing father. In 1716 Peter ordered his son to join him with the army, instead, Aleksey fled the country to Austria. The scandal proved to be the final straw and once Aleksey was tricked into returning to Russia he was put on trial, tortured and eventually died in prison.

Empire

In 1721 the Treaty of Nystad was signed between Russia and Sweden which brought the Great Northern War to an end. Russia was the main benefactor under the agreement as Sweden formally recognised Russia’s claim to the whole of Ingria, Estonia and Livonia, plus Priozersk and Vyborg. Following the treaty and the incorporation of the new territories, Peter proclaimed the beginning of the Russian Empire and he adopted the title of emperor rather than tsar, although the word ‘tsar’ is still commonly used to refer to the ruler of the Russian Empire.

Russo-Persian War

In 1722 Peter launched a naval campaign against Persia with the support of fellow Orthodox leaders of Georgia and Armenia. The newly established Caspian Flotilla from Astrakhan was joined by the Russian Army and Cossacks along with Georgian and Armenian support and were able to capture Persian territory in the Caucasus, including Derbent and Baku, from the Persians who were forced to sue for peace and recognise Russia's gains in the Caucasus in 1723 when the Ottomans invaded Persia.

Death of Peter the Great

Peter suffered bouts of ill health throughout his life and in the winter of 1725 he once again fell ill with bladder problems. He died in February 1725 while allegedly trying to write a note on a scrap of paper, what he managed to complete was “Leave all to”. The great reformer and first emperor was dead, but he left behind an empire facing Europe from its new capital of St Petersburg; the old ways of Muscovite Russia were a thing of the past.

Reign of Catherine I

Back in 1704 while on campaign in Livonia Peter had met a beautiful peasant called Marta Skavronskaya. In 1707 Peter and Marta were secretly married with Marta adopting Orthodoxy and the name Yekaterina Alekseevna. Yekaterina had a soothing influence on Peter and bore him several children although only two daughters survived into adulthood: Anna and Yelizaveta. An official marriage ceremony took place in 1712 in St Petersburg’s St Isaac’s Cathedral and in 1721 Peter named her empress consort of Russia. She is generally known in English as Catherine I.

After Peter’s death Catherine was named the new empress, largely thanks to the manoeuvrings of Peter the Great’s closest friend and advisor - Prince Aleksandr Menshikov who sought to rule Russia in her name as the head of the newly created Supreme Privy Council. Menshikov’s schemes went to plan and he retained his important position throughout Catherine’s reign which allowed him to continue his corrupt ways. One personal policy of Catherine though was the reducing of military spending which in turn brought down taxes which earned the first empress popularity. Catherine is also remembered for the Catherine Palace which she had constructed on the outskirts of St Petersburg in Tsarskoe Selo.

Reign of Peter II

After Catherine I's death in 1727, the throne passed to the only male-line grandson of Peter the Great - Pyotr Alekseevich who became Emperor Peter II. Menshikov hoped to keep his influence by marrying his daughter Maria to the new emperor. However when Menshikov fell ill Peter and his advisors seized their moment and stripped Menshikov his rank and had him exiled to Siberia. Peter II moved the capital back to Moscow after his coronation in the city in 1728. In 1730 on the day he was supposed to marry Yekaterina Dolgorukova - an attempt by the Dolgorukovs to secure their own position in court - Peter II died aged just 14.

Empress Anna

After Peter II, the Supreme Privy Council hoped to pull off a coup by offering Peter the Great's half-niece Anna the crown. Anna was the daughter of Tsar Ivan V and a widow of the duke of Courland where she was ruling. Anna accepted the offer and even signed a list of conditions limiting her powers in favour of the Privy Council. The Privy Council, however, was mistaken in their belief that Anna would feel indebted to them for offering her the throne and upon becoming empress she proceeded to disband the council and ignore the conditions she had agreed to, thereby confirming the autocratic rule. Anna also returned the capital back to St Petersburg.

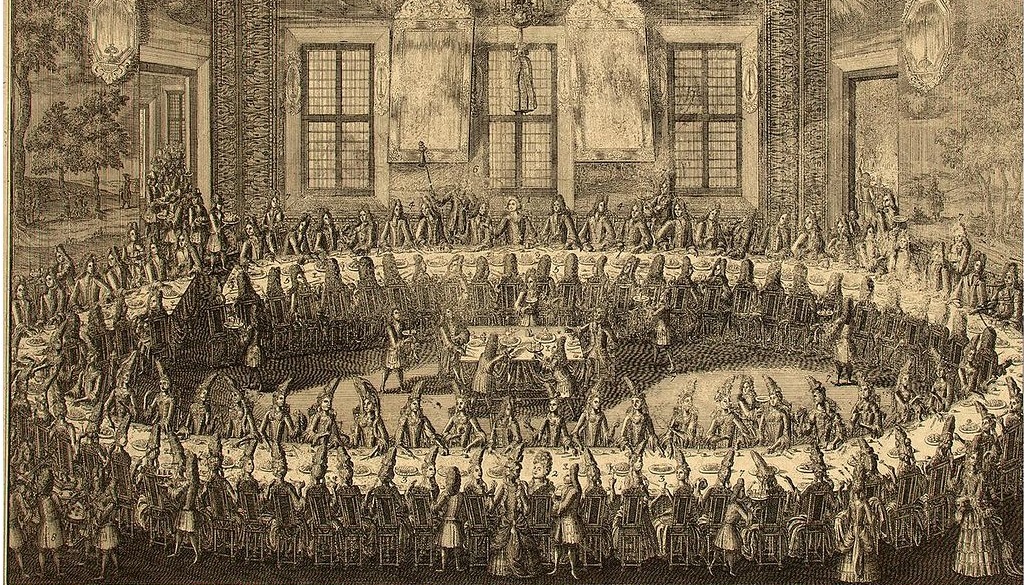

Anna's reign is remembered rather unfavourably and for the influence of ethnic Germans at the imperial court as Anna brought with her from the Duchy of Courland (now in modern-day Latvia) several ethnic German advisors including Ernst Johann Biron who was possibly her lover. Biron became the most powerful man in the country. Under Biron and Anna, a secret police service was established which resulted in over 1000 people being executed and tens of thousands of people being exiled to Siberia, while others were subject to cruel and degrading punishments. In addition, Anna seemed to enjoy humiliating her subjects, including the disabled and high-ranking Russian nobility. On a plus note Anna was a great supporter of art and culture and continued to fund the Academy of Sciences.

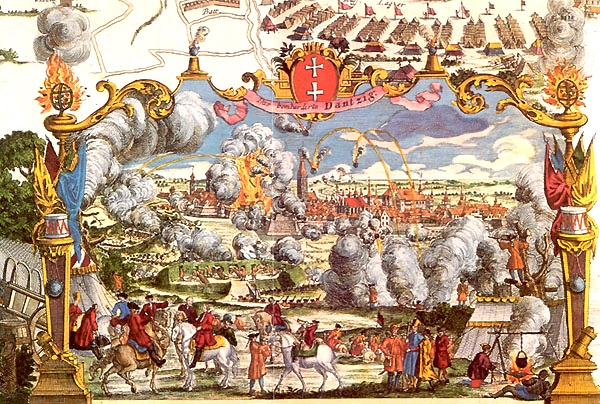

War of Polish Succession

Russia was drawn into the War of Polish Succession in 1733 supporting the claim of Elector Friedrich August II of Saxony, the eventual victor in the war becoming King August III of Poland. For its support King August III allowed Anna to name Biron the new duke of Courland in 1737 following the extinction of the ruling house of Kettler.

Russo-Turkish War

In 1735, in response to Crimean raids on Ukraine, Russia declared war on the Ottoman Empire, the suzerain of the Crimean Khanate. Beforehand Russia gave back the Caucasian possessions it had won from Persia in order to keep Persia from allying with the Ottoman Empire. Russia hoped to win back Azov and increase its territory providing access to the Black Sea. Russia initially saw success and occupied the Crimean capital of Bakhchisarai but was subsequently forced to retreat back to Ukraine due to a lack of supplies. The Russians were later though able to capture Azov in 1736. Russia's ally of Austria was forced to sue for peace after losing the Balkans to the Ottomans and in October 1739 signed a treaty with the Turks who recognised Russia's possession of Azov, although Crimea and Moldova remained under Ottoman control. Both the Polish and Ottoman wars proved immensely costly for Russia.

An Infant Emperor

Empress Anna died in 1740. Previous to this, in an attempt to secure the throne for the descendants of her father Ivan V, rather than those of Peter the Great, Anna named her grand-nephew Ivan her heir. Ivan was the son of Duke Anthony Ulrich of Brunswick and Princess Elisabeth of Mecklenburg-Schwerin (the daughter of Anna's sister Grand Duchess Yekaterina Ivanovna), who converted to Orthodoxy in 1733 and took the name Grand Duchess Anna Leopoldovna of Russia. He was only a few months old when he was named Emperor Ivan VI of Russia. Originally Biron was named his regent but in just over a week Biron was ousted and Ivan's mother Anna Leopoldovna became regent and ruled along with the vice-chancellor Andrey Osterman.

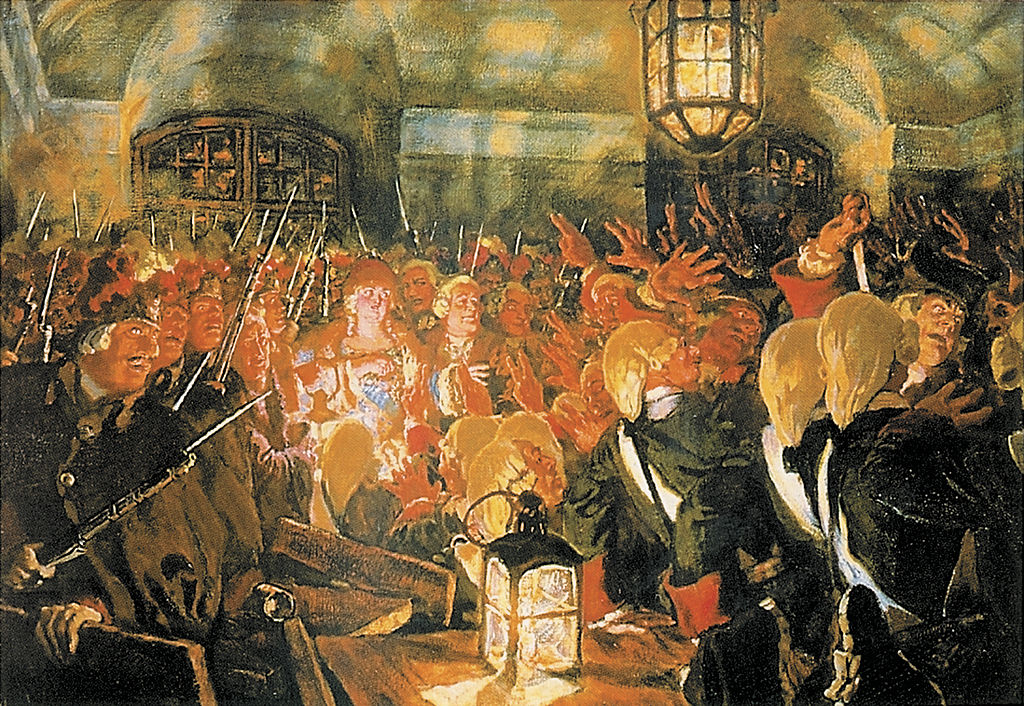

Coup of Grand Duchess Yelizaveta Petrovna

In December 1741 the oldest surviving daughter of Peter the Great, Grand Duchess Yelizaveta Petrovna, saw her chance to take the throne of her father after having been gathering support for her cause since the reign of her cousin Anna. Yelizaveta enjoyed special popularity among the Preobrazhensky Regiment whose support would prove vital. Yelizaveta led the regiment to the Winter Palace where the infant Ivan VI was arrested along with his parents. Without any bloodshed Yelizaveta took the throne and was crowned empress in Moscow the following year, commonly known in English as Empress Elizabeth.

Reign of Elizabeth

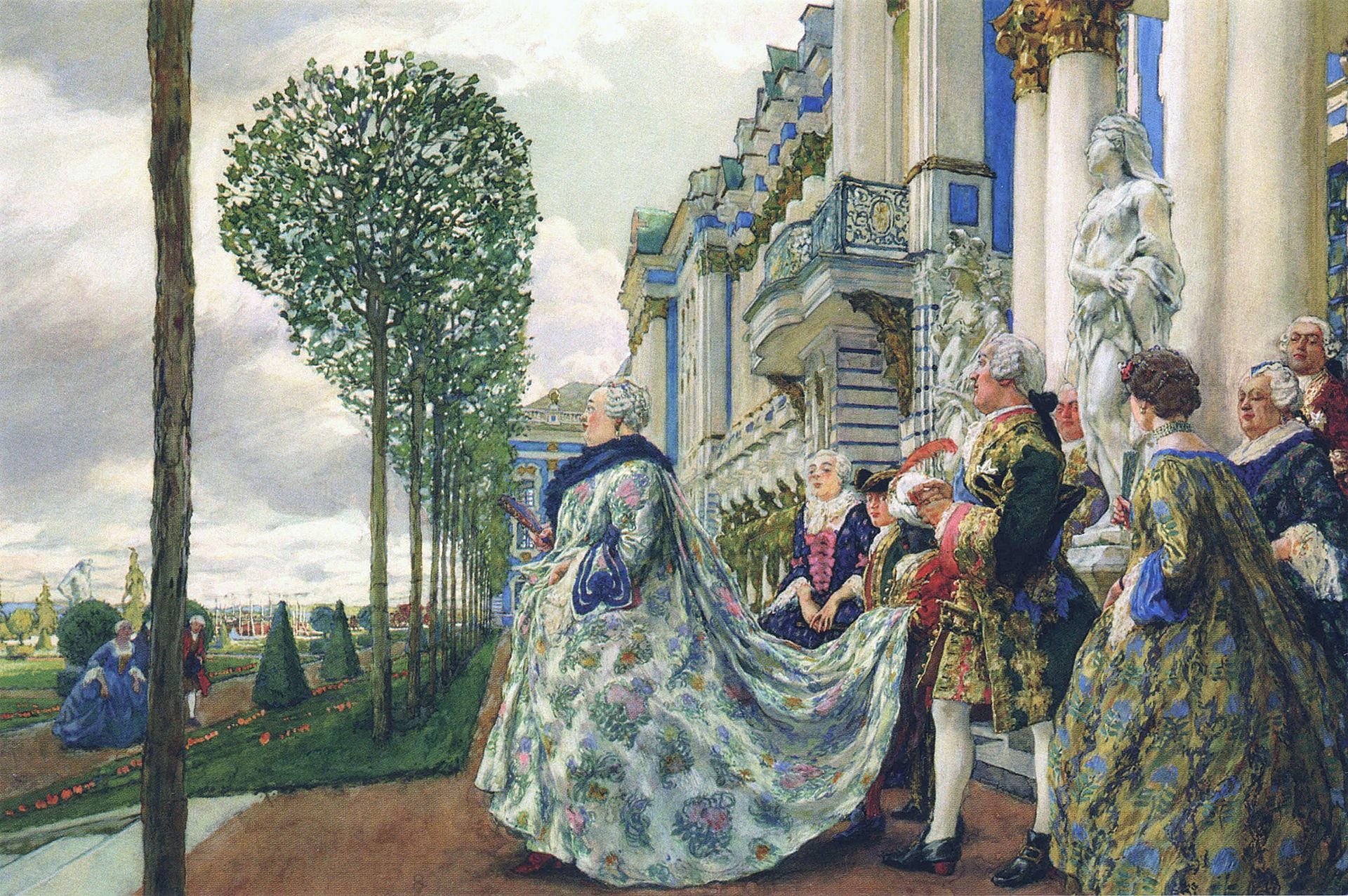

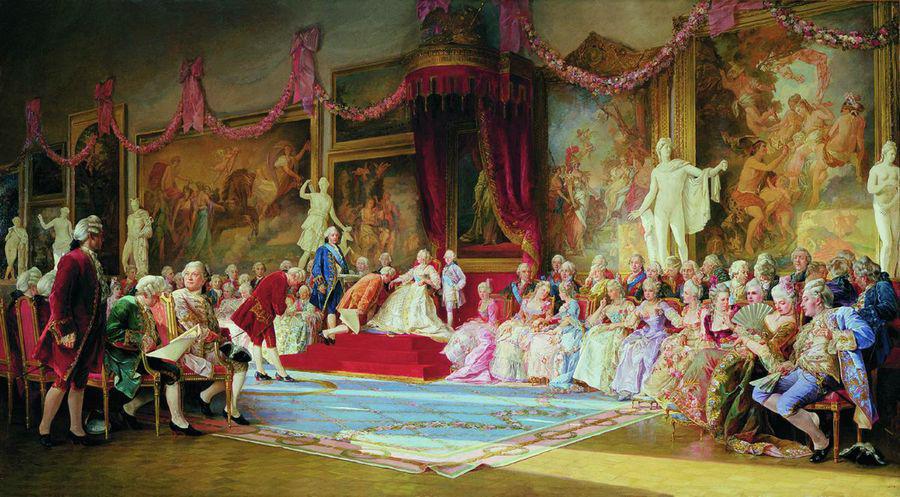

Empress Elizabeth had a reputation of being vain and jealous and is remembered for her love of high-society and balls, where she frequently wore male clothing, but she also had the sense to put able advisors in place to assist her with ruling the country. Upon coming to power Elizabeth acknowledged the end of the influence of ethnic Germans and installed ethnic Russians of the Orthodox faith in positions of power and reinstated the Senate.

Seven Years War

In 1757 Russia entered the Seven Years War on the side of France and Austria against Prussia. The Russian army marched on Königsberg and inflicted a crushing defeat on King Frederick the Great of Prussia's troops at the battle of Kunersdorf in 1759.

Elizabethan Baroque

Elizabeth was a committed supporter of the arts, especially of the theatre and music. She also had a love for architecture and commissioned the building of many new churches. One of her favourite architects was the Italian Bartolomeo Rastrelli who was responsible for the construction of St Petersburg's Smolny Convent and the renovation of the Winter Palace in St Petersburg and the Catherine Palace in Tsarskoe Selo. The style of architecture popular during Elizabeth's reign has since become known as Elizabethan baroque. Elizabeth is also remembered for promising not to apply the death penalty during her reign and for keeping her word, although torture and other brutal forms of punishment were still used.

Elizabeth’s Heir

Although there are reasons to believe Elizabeth married a Cossack by the name of Aleksey Razumovsky, who was famed for his beautiful singing voice, and possibly even had a child with him, Elizabeth never officially married and left no legitimate heirs. Fearing a plot to return Ivan VI to the throne, who was still imprisoned in Schlisselburg, Elizabeth took steps to resolve the matter of her succession by bringing her nephew Duke Charles Peter Ulrich of Holstein-Gottorp to Russia in 1742. She also found a wife for him in the form of Princess Sophia Augusta Frederica of Anhalt-Zerbst. Peter converted to Orthodoxy (in an official sense at least) and took the name Pyotr Fyodorovich, while Sophia took the name Yekaterina Alekseevna.

Reign of Peter III

Elizabeth died in 1761 (1762 in the new style of dates) and was succeeded by her designated heir - her German-born nephew, who became Emperor Peter III. From the very outset, Peter was unpopular with almost everybody due to his character, often being described as a Russophobe, an idiot and a drunk. He was especially unpopular with his educated and Russophile wife Catherine, who was forced to put up with his erratic and childish behaviour. Peter’s domestic reforms were by the standards of the time democratic and progressive which in turn led to further unpopularity among the ruling elite. His foreign policies proved even more divisive as immediately in his reign in January 1762 Peter decided to make peace with his hero Frederick the Great of Prussia as Russian troops were approaching Berlin and ultimate victory.

Overthrow of Peter III

From the very beginning, the days of Peter’s reign were numbered. The inevitable plot to overthrow him came in July 1762 and was led by Aleksey Orlov of the Imperial Guards and who was also the lover of Peter’s wife Catherine. Catherine played a part in the plot fearing that unless she acted she would most likely be sent to a convent by her husband or worse. The coup was successful and Peter was forced to abdicate and was imprisoned in the palace at Ropsha, before being murdered a few days later. In his place, Catherine, despite not having a drop of Romanov or even Russian blood, was named empress.

Catherine the Great

Catherine II has gone down in history as Catherine the Great and as the most enlightened of rulers of Russia, whose reign is seen as a golden age as the empire grew in size, population and influence. As well as being a great supporter of the arts, sciences and education, Catherine was also a brilliant administrator. In 1776 administrative-territorial reforms begun which saw the country divided into governorates and vice-royalties. Many settlements were also awarded city status and granted coats of arms and regulated city plans were approved. Another reason which led to Catherine being known as the Great is that her reign saw massive territorial expansion. Catherine also has a skill for selecting talented men to help her in ruling the country, several of them also became her lovers, most famously Grigory Potyomkin whom she may have even secretly married. Much is made of Catherine’s lovers, but in reality, it was not unusual for monarchs to take a string of lovers, what is different is that usually, the monarchs were male. More of the deprived stories about Catherine’s sexual appetite were fabricated by here enemies, including by her son who never forgave her for her role in the murder of her husband, his father.

However, Catherine can only really be described as an enlightened despot as her liberal ideas were not always put into practice. This is especially clear with the status of the serfs. Although the idea of abolishing serfdom was explored during Catherine’s reign, nothing came of it as the prospect of liberating the uneducated serfs and removing the free labour of the landed gentry proved too big an issue to handle.

Catherine was also ruthless in terms of her competition. In 1764 a plot to free Ivan VI from his prison in Schlisselburg was foiled which resulted in the death of the 23-year old former emperor, who had spent most of his life locked away. Later in her reign, Catherine also had a woman who was claiming to be the daughter of Empress Elizabeth brought to Russia and imprisoned in the Peter and Paul Fortress where she is said to have drowned in 1775 (although other theories say that she was actually allowed to live out the rest of her life in secret at a convent). The full facts of this story remain unknown and this mysterious woman has gone down in history as Princess Tarakanova, after the Russian word for cockroach.

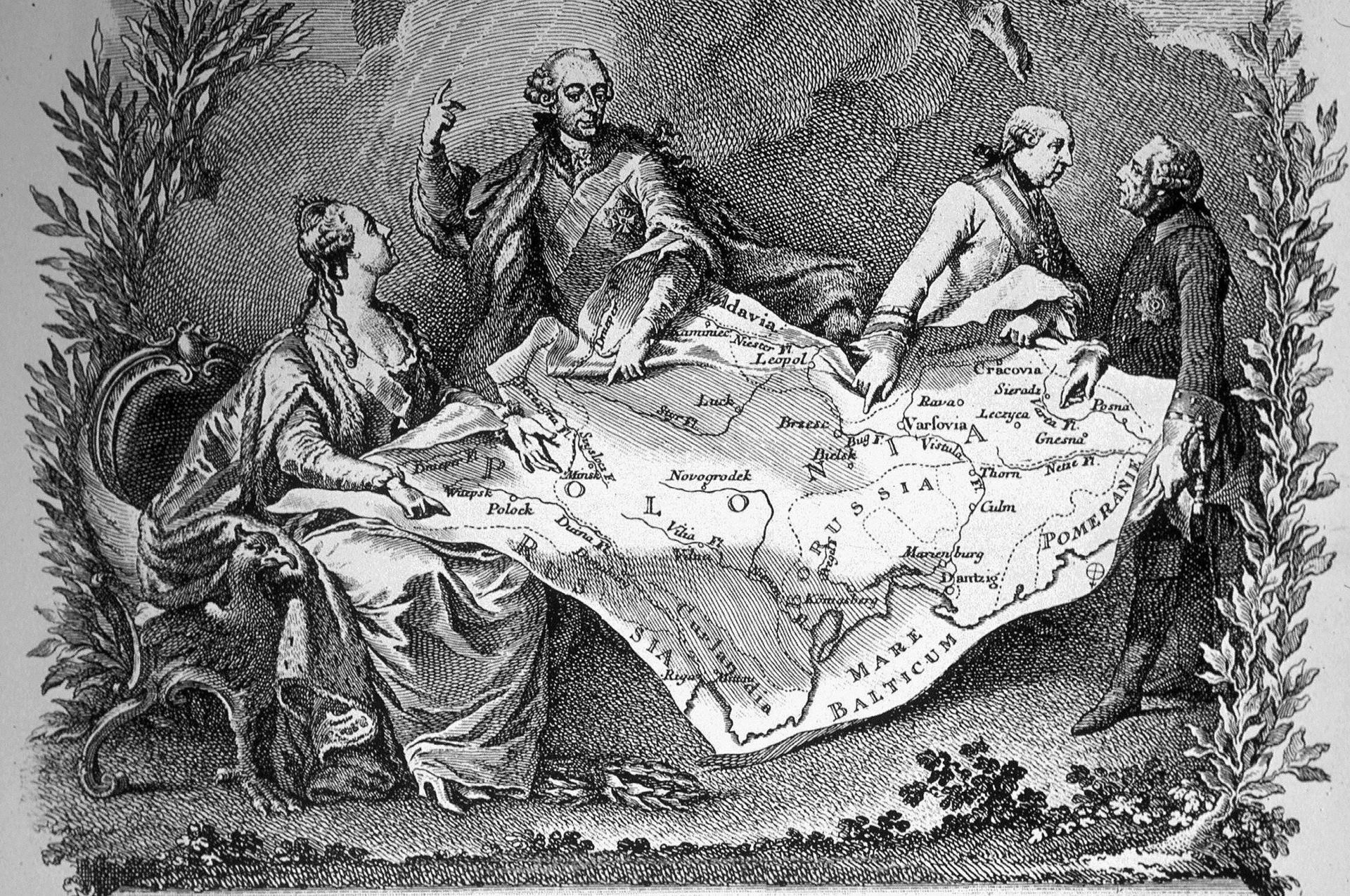

Partition of Poland

Under Catherine’s reign, Russia extended her borders to the west at the cost of Poland where Catherine was successful in having her former lover Stanisław Poniatowski elected king in 1764. Poland was subsequently ruled by the Russian ambassador which led to protests and then the First, Second and Third Partitions of Poland in 1772, 1793 and 1795 respectively. As a result of the partitions, Poland lost its independence and Russian gained the territory consisting of modern-day Belarus, the Baltic States and Western Ukraine with the exception of Galicia. This expansion meant that the Russian Empire gained large populations of Poles, Ukrainians, Lithuanians and Jews, in respect of whom a law was enacted in 1792 which only permitted Jews to live in the western part of the empire which became known as the Pale of Settlement.

Russo-Turkish Wars

In 1768 the Russo-Turkish War broke out and Russia’s success in the war, especially the decisive Russian victories at the Battle of Kagul in 1770 and the Battle of Chesma in 1771, culminated in a peace treaty in 1774 which was beneficial for Russia and saw Russia increasing its influence over South Ukraine and Crimea. In 1783 Catherine went a step further and annexed the Crimean Khanate which eventually sparked another war with the Ottoman Empire in 1787. The second Russo-Turkish war during Catherine’s reign was equally successful for Russia and remembered for the successful siege of Ochakov in 1788 and the capture of the Izmail Fortress by famous Russian commander Aleksandr Suvorov in 1790. Peace was reached in 1792 which saw the Ottoman Empire recognising Russia’s incorporation of South Ukraine and Crimea. However, Catherine’s dream of liberating Constantinople from the Turks was never realised.

Pugachev Rebellion

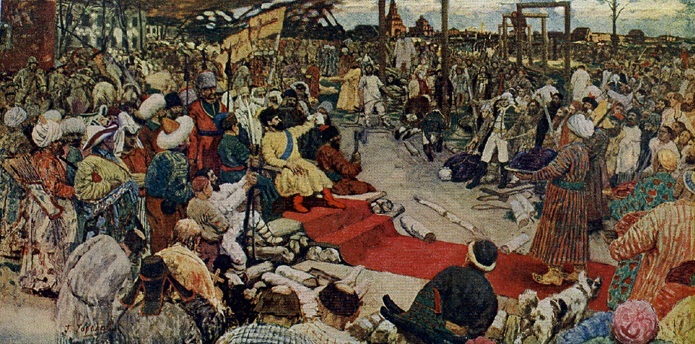

The biggest threat to Catherine’s reign came in the form of a disgruntled Cossack named Yemelian Pugachev. In 1770, after being refused permission for home leave from the army, Pugachev fled to join a group of independent Cossacks. He was arrested several times but always managed to escape and became a fugitive among the Yaik Cossacks and was sheltered by Old Believers. Pugachev was able to unite a large group of Cossacks, peasants, Old Believers, Bashkirs, Tatars and Kalmyks, who were all dissatisfied with Russian rule. By claiming to be Peter III who had somehow survived the coup of his wife, Pugachev became the leader which turned widespread dissatisfaction into a full-scale uprising in 1773.

The uprising was hugely successful and whole sways of Russia’s lower Volga region and parts of Western Siberian, including large cities such as Penza, Samara, Saratov, Tsaritsyn, Orenburg, Ufa and Yekaterinburg, supported Pugachev, who in turn set up his own alternative form of government. The state response to the threat was so harsh and brutal that it proved counter affected and caused more people to turn to Pugachev who promised freedom for serfs and minorities.

In July 1774 Pugachev achieved his greatest victory when his troops captured the major city of Kazan, with the exception of the kremlin. However, upon taking Kazan, Pugachev had overstretched himself. Government troops were able to recapture the city and Pugachev was forced to flee. The tide had now turned in favour of the Russian army led by General Pyotr Panin and General Ivan Michelson. Pugachev and his men attempted to regroup in Tsaritsyn where the government troops inflicted a crushing defeat on them in August 1774. In September 1774 Pugachev’s own men betrayed him and delivered him to the Russians. He was placed in a metal cage and delivered firstly to Simbirsk and then to Moscow where in January 1775 he was beheaded then drawn and quartered on Bolotnaya Ploschad.

Death of Catherine

Catherine the Great died in 1796 and was succeeded by her son Pavel – known as Paul in English. Catherine and Paul both detested and distrusted each other, Catherine even alleged that Paul’s father was not Peter III and it is thought she intended to name Paul’s eldest son Aleksandr Pavlovich (the future Alexander I) as her successor. The mutual dislike for one another is often explained by the fact that as a baby Paul was taken for his mother by Empress Elizabeth. One of Paul’s first acts was to destroy his mother’s testament and introduce a new law establishing the principle of primogeniture where an emperor is survived by his next male heir, and women can only be considered if there are no surviving male Romanov heirs. As an act of revenge, Paul had his father reburied in the Ss Peter and Paul Cathedral next to his mother and ordered that Count Aleksey Orlov (Peter III’s probable murderer) carry the coffin.

Military Reforms of Paul

Although it was claimed that Paul was not the son of Peter III, the fact that he resembled him and shared his eccentricities and love for military pomp and ceremony suggests that the claim was false. In turn, he shared no characteristics or interests with his mother, practically opposing everything she supported. He quickly brought an end to the Persian Campaigns supported by his mother to extend the empire southwards, in order to concentrate more on Europe. Upon becoming emperor, Paul reorganised the army along Prussian lines and introduced new uniforms which although may have looked impressive were uncomfortable and impractical. Even the distinguished general Aleksandr Suvorov criticised the reforms which earned him dismissal from the army.

Italian and Swiss Campaigns

In the face of the rise of the French Republic and anti-monarchy sentiment, Russia joined a coalition against France. In 1799, outraged at the French capture of Malta (Paul was obsessed with the Knights Hospitaller and was even made grandmaster in 1798), Russia declared war and met the French in the Italian and Swiss campaigns of the French Revolutionary awards. For this Paul was forced to bring back Suvorov who continued his record of never losing a single battle – an almost unique feat in history. The campaign famously included a Hannibal-like crossing of the Alps by Suvorov and his men to escape destruction by a much larger and stronger French force. Despite the heroic feats of Suvorov, overall the Italian and Swiss campaigns remained fruitless for Russia and the scene was set for a further confrontation between Russian and France.