17th Century

The beginning of the 17th century is known as the Time of Troubles which lasted from the death of Tsar Feodor – the last Ryurikid tsar – until the ascension of Tsar Michael – the first Romanov tsar. During this period various pretenders claimed the throne and the very existence of Russia was at threat. After the Troubles had ended the country gradually recovered with the Romanovs at the helm. The century ended with the reign of Peter the Great who had set Russia on a course looking westwards.

Great Famine

In 1601 cold weather led to a crop failure which was followed by bad harvests in 1602 and 1603. During the resulting famine, Tsar Boris tried to help his starving subjects by opening the state grain reserves in Moscow. In fact this just made events worse as it attracted more people from surrounding towns to Moscow and put even more pressure on the capital. In all millions of Russians starved to death and the survivors revolted over the handling of the situation. Many Russians even believed God had caused the famine due to Boris' role in the death of Tsarevich Dmitry, today geologists believe that the famine was in fact due to the volcanic winter caused by the eruption of Huaynaputina in Peru.

The Time of Troubles

The period of Russian history since the fall of the House of Ryurik and the rise of the House of Romanov is called the Time of Troubles and the period became especially troublesome after the Great Famine and the first rumours started to spread that Tsarevich Dmitry did not actually die in Uglich but managed to escape. In 1603 a man calling himself Dmitry appeared in Poland and won the support of Poland to reclaim the throne of his father Ivan the Terrible. In fact this man was almost certainly not Dmitry and most likely even his Polish supporters did not believe he was, but supported him to gain influence over a weakened Russia. It is thought that this man was a runaway monk called Grigory Otrepiev from a monastery in Moscow's Kremlin, who allegedly had links with the Romanovs. In history he has become known as the First False Dmitri.

Later in 1603 the First False Dmitri crossed the Polish-Russian border with his army. At first Dmitry won the support of several border cities and the Cossacks. In 1604 Dmitri was even able to defeat Tsarist troops outside Novgorod-Seversky. Later the cities of Putivl, Ryslk, Sevsk, Kursk and Belgorod declared for Dmitry - creating a route east to Moscow. Dmitry's luck eventually seemed to have ran out in 1605 when he and his army were eventually defeated in battle by the army of Tsar Boris outside Sevsk. Despite the setback further cities declared their support for the pretender including Oskol, Voronezh, Yelets and Livny. However the decisive event which changed everything came in April 1605 when news reached Dmitry that Tsar Boris had died.

The Pretender on the Throne

Boris Godunov was succeeded by his 16 year old son Feodor who became Tsar Feodor II. A group of boyars in Moscow saw that the days of the Godunov family were numbered and took action. In June 1605 they imprisoned and subsequently murdered Tsar Feodor and his mother. Dmitry was proclaimed the legitimate tsar and in the same month he jubilantly entered Moscow and was crowned Tsar Dmitry. Dmitry immediately set about securing his reign. He brought Maria Nagaya (widow of Ivan the Terrible and the mother of the real Tsarevich Dmitry) to Moscow where she recognised him as her son, although she probably had no other option. Patriarch Job on the other hand refused to recognise him and was subsequently illegitimately replaced by Ignatius who was able to recognise Dmitry. Dmitry also allowed several noble families who were exiled by Boris Godunov to return to Moscow. This included Filaret Romanov whom he named Metropolitan of Rostov.

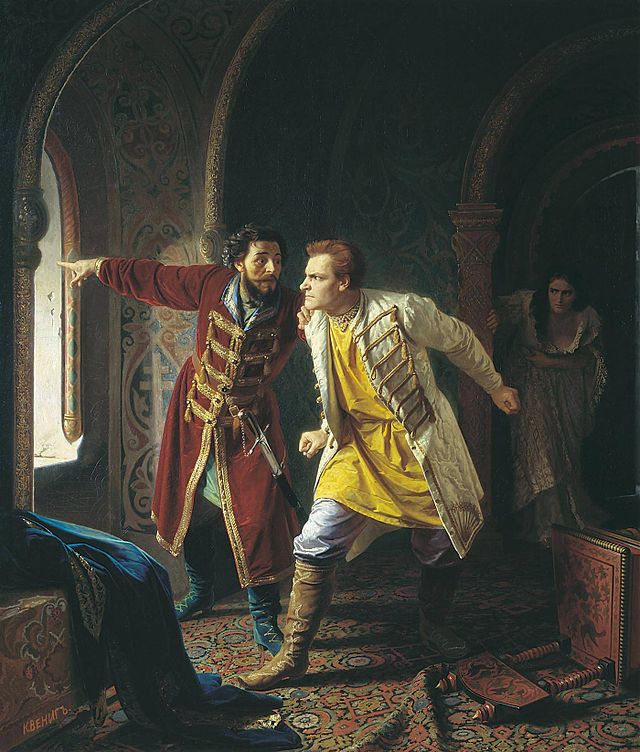

In May 1606 Dmitri married Maryna Mniszchówna, the daughter of a powerful Polish nobleman. This marriage was unpopular among the Russians as Maryna was Polish and even refused to convert from Catholicism to Orthodoxy. The Russians also suspected that Dmitry had promised the pope that he would convert Russia to Catholicism. This would be the downfall of Tsar Dmitri as a group of boyars, led by Vasily Shuisky, began to plot against him. Dmitry's Polish troops also did not help the matter as they went about committing crimes in Moscow angering the local population. Two weeks after Dmitry's marriage to Maryna, the boyars acted. They stormed the Kremlin and killed Tsar Dmitry as he tried to escape. According to legend they then cremated his body and put the ashes in a cannon and fired them towards Poland. Maryna was spared and eventually sent back to Poland, her father was exiled to Yaroslavl.

Tsar Vasily IV and the Second False Dmitry

After the fall of the First False Dmitry, Vasily Shuisky - a leading boyar and a member of the Suzdal branch of Ryurikid princes - was proclaimed tsar in May 1606. However Vasily IV enjoyed little authority and in fact his rule was not even recognised over the whole of Moscow let alone Russia. In 1607 a second false Dmitry appeared on the scene and quickly captured Bryansk and surrounding towns with Polish aid. By 1608 the army of the Second False Dmitry was marching on Moscow and managed to defeat the army of Vasily IV outside Bolkhov. The Second False Dmitry set up camp in Tushino on the outskirts of Moscow where he was "reunited" with Maryna Mniszchówna who recognised him to be her husband who had somehow miraculously managed to escape. This was despite the fact that he was said to bare absolutely no resemblance to the First False Dmitry.

Many important cities recognised the Second False Dmitry and in effect Vasily was only recognised as the legitimate tsar in parts of Moscow, Kolomna, Smolensk, Ryazan, Nizhny Novgorod and the Troitse-Sergiev Monastery which was as a result was besieged by the Polish in September 1608. Filaret Romanov, the metropolitan of Rostov, also fell into the pretender's hands who named him the new patriarch as opposed to Vasily Shuisky's candidate of Hermogenes who was installed to replace Ignatius in 1606.

Swedish Intervention

King Charles IX of Sweden was watching the events in Russia closely and in 1610 he saw an opportunity and sent an army led by Jacob De La Gardie to capture Staraya Ladoga. This victory in turn led to Novgorod inviting the Swedish king to send one of his sons to rule in Novgorod. De la Gardie proceeded to enter Novgorod. Tsar Vasily IV understood the danger and decided peace would need to be made with Sweden before he could deal with the threat posed by the pretender. Therefore in 1609 Vasily IV sent his nephew Prince Mikhail Vasilievich Skopin-Shuisky to negotiate with the Swedes.

As a result an alliance with Sweden was entered into, at the cost of ceding Korela to Sweden. Skopin-Shuisky and De la Gardie then led their respective armies to Moscow. On the way they recaptured the city of Toropets from Polish troops supporting the Second False Dmitry in May 1609, followed by Torzhok in June, Tver in July, Kalyazin in August and Pereslavl-Zalessky and Aleksandrova Sloboda in September. The joint army then met the Polish troops of Hetman Jan Sapieha, which had been involved in besieging the Troitse-Sergiev Monastery, outside Aleksandrova Sloboda and defeated them, which in turn led to the siege of the Troitse-Sergiev Monastery being broken in January 1610. Finally in February Dmitrov was liberated. Shortly after his return to Moscow in March as a hero, Skopin-Shuisky unexpectedly died after drinking wine at a celebration. It is believed he is poisoned by his nephew Dmitry Shuisky, the brother of Tsar Vasily, who feared and was jealous of his cousin's successes.

Polish Intervention

In response to the alliance with Sweden, King Sigismund III of Poland decided to take a more active role in Russian events. Poland officially declared war and began besieging Smolensk in September 1609. This in turn considerably weakened the Second False Dmitry as his Polish supporters abandoned him to fight alongside their king. The Second False Dmitry was eventually forced to flee his base in Tushino for Kaluga due to his lack of support and the successes of Skopin-Shuisky and De la Gardie. He was eventually killed by one of his own men in December 1610.

In July 1610 the Polish army met the Russian army with their Swedish allies at the Battle of Klushino which was fought outside Smolensk. This time instead of Skopin-Shuisky the army was led by Dmitry Shuisky and the battle resulted in a Polish Victory and shame for the tsar's brother. The defeat was the death knell for Vasily IV who in August was overthrown by a group of seven boyars. The Polish victors proceeded to march on Moscow and on its outskirts set up a base in Khoroshyovo, while the forces of the Second False Dmitry re-gathered in Kolomenskoe. The capital was thereby surrounded and the nominally ruling seven boyars decided to enter into talks with the Polish, seeing the pretender as the greater of two evils. A compromise was reached whereby the Polish king's son Władysław would be named tsar and Polish troops would be allowed to enter the kremlin. Vasily was later sent to Warsaw as a prisoner and by October Polish troops had entered Moscow.

After four previous attacks and 20 months of siege the Polish were eventually able to capture the Smolensk Kremlin in June 1611 after a runaway traitor told the Polish of a weakness in the defences.

The First People's Volunteer Army

While still in Smolensk King Sigismund of Poland decided that it would actually be better if he was made tsar instead of his son. This proved to be the final straw for a potential Polish-Moscow alliance and the Moscow boyars began considering alternatives. In 1611 Filaret Romanov, who had been named patriarch by the Second False Dmitry was arrested by the Polish and sent to Poland, partly as his own family were seen as potential rivals to the Polish. By now the Polish troops in Moscow were becoming more and more viewed as occupants. This view was clearly held by Patriarch Hermogenes who wrote and sent letters to various parts of the country explaining how the Polish had desecrated holy sites in Moscow and how the Russian people must rise up against the occupants to save their country from complete collapse.

Inspired by one of Hermogenes' letters, Prokopy Lyapunov founded in Ryazan what has become known as the First People's Volunteer Army. By March 1611 the army had reached Moscow and an uprising quickly turned into the siege of the Moscow Kremlin. In an attempt to regain control the Polish attempted to force Patriarch Hermogenes to sign a letter denouncing the anti-Polish actions. Hermogenes refused and was subsequently imprisoned. In July the uprising suffered a severe setback when Lyapunov was killed by one of his Cossack allies, who feared Lyapunov would betray the Cossacks by putting restrictions of the Cossacks' freedoms.

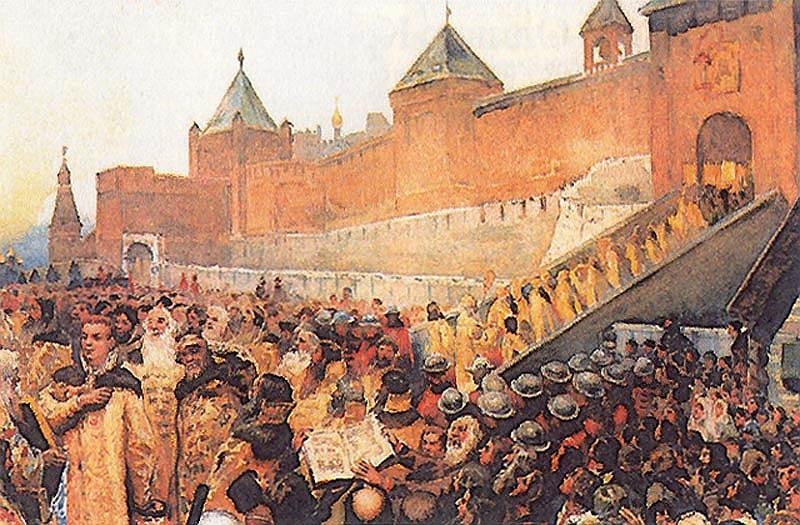

The Second People's Volunteer Army

In August 1611 another of Hermogenes' letters was received in Nizhny Novgorod by an elder of the city called Kuzma Minin. Minin used part of his own funds to raise the Second People's Volunteer Army which gathered in Nizhny Novgorod. In October its future leader Prince Dmitry Pozharsky, who had previously fought alongside the army of Prokopy Lyapunov, arrived in the city after answering Minin's invitation. In March 1612 the army was ready and set out from Nizhny Novgorod following the course of the River Volga before eventually reaching Yaroslavl where it remained until the end of July. By August the army had reached the Troitse-Sergiev Monastery and was in sight of Moscow by the end of the month. For the next two months the volunteer army besieged the Polish walled up in the Moscow Kremlin. In the beginning of November the surviving Polish troops who had not yet died of starvation had no alternative but to surrender. Moscow had been liberated, unfortunately though too late for Patriarch Hermogenes who had died of starvation in prison.

Election of a New Tsar

In March 1613 the Zemsky Sobor met in order to elect a new tsar whose task it would be to rebuild the country. This burden fell on the 16-year-old Mikhail Romanov - the son of Filaret Romanov who was still in prison in Poland. Mikhail Romanov was at the time at the Ipatiev Monastery in Kostroma with his mother and a delegation was immediately dispatched to inform him of the decision and bring him back to Moscow. However Polish interventionists who were still a force to be reckoned with in parts of the country learned of the new election and also set out for Kostroma. According to a famous legend the Polish employed the services of a Russia named Ivan Susanin to guide them through the dense forests to Kostroma. Susanin agreed but really led them deeper and deeper into the forest. When the Polish understood they had been tricked they killed Susanin but nevertheless perished lost in the forest.

In the meantime the delegation from Moscow had reached the Ipatiev Monastery and Mikhail reluctantly agreed to become tsar (he is usally known as Tsar Michael in English) after the delegation informed him that his refusal would mean the end of Russia. From Kostroma Tsar Michael left for Moscow passing the important cities of Nizhny Novgorod, Yaroslavl, Rostov, Vladimir, Suzdal and Sergiev Posad en route to show the people a new tsar had been elected.

Peace with Sweden

Even after the election of a new tsar and the end of the Time of Troubles Russia was not fully at peace. In the north the Swedish troops led by De la Gardie still held Novgorod and much of the area known as Ingria. In 1613 the Swedes began besieging Tikhvin but were repelled by the Russians. They had more success in 1614 when they captured Gdov. The next target was Pskov but the city managed to hold out until peace with made Sweden in 1617. The Treaty of Stolbovo was signed which saw Russia hand over Ingria to Sweden, which included Ivangorod, Yama, Koporye and the Oreshek Fortress, in return for Novgorod.

Peace with Poland

Polish troops were also at large in Russia following the end of the Time of Troubles. One group of soldiers and outlaws, which became known as the Lisowczycy after its leader Aleksander Lisovski, was responsible for bringing havoc across the country - besieging, capturing and burning many cities between 1615 and 1616 including Bryansk, Rzhev, Kursk and Bolkhov. In 1617 Prince Władysław led an army into Russia to try and force his claim to the Russian throne. The army managed to capture Dorogobuzh and Vyazma, but were defeated en route to Mozhaisk and had to give up their advance on Moscow. In the meanwhile the Lisowczycy relieved the regular Polish troops stationed in Smolensk which was being besieged by Russian troops. One final attempt to capture Moscow came in 1618 but when this failed, peace negotiations were began and a treaty was signed. Following the peace with Poland Filaret Romanov, the tsar's father, returned to Moscow after years of imprisonment in Poland. Upon his return he was installed as patriarch and in practice became a co-ruler alongside his son up until his death in 1633.

The Early Reign of Tsar Alexis

The first Romanov tsar died in 1645 and was succeeded by his son Aleksey Mikhailovich (Tsar Alexis). During the early reign Tsar Alexis, the young tsar was under the influence of the boyar Boris Morozov, who managed to gain his position by arranging the marriage of the tsar to Maria Miloslavskaya, while Boris himself married Maria's sister Anna. Boris was what was seen as a typical boyarn, more interesting in filling his pockets rather than serving the state. It appeared that Morozov's downfall came in 1648 when riots against the prices of salt - known as the Salt Riot - broke out in Moscow, but Morozov secretly returned from exile several months later. In 1649 a new legal code was introduced which consolidated Russian serfdom, meaning that the serfs were now fully considered the property of the land-owing nobility. Under the new law escaped serfs could be found and forced to return to their master indefinitely, previously there was a 10 year limit.

War with Poland and Sweden

In 1648 Hetman Bohdan Khmelnytsky of the Zaporozhian Cossacks led his Cossacks and local Ukrainian peasants in a successful rebellion against Polish and Lithuanian magnates. During a meeting of the council of the Zaporozhian Cossacks and representatives of Tsar Alexis in Pereyaslavl in 1654, the Cossacks agreed to the protection of Russia which led to Left-Bank Ukraine (i.e. the part of Ukraine to the east of the Dnieper) being incorporated into Russia. Russia subsequently declared war on Poland, which was now in a period of its history known as the Deluge. The first years of the war proved extremely successful for the Russians with the liberation of Smolensk and the capture of several major Lithuanian cities. Sweden decided not to miss the opportunity and also invaded Poland in 1655.

While Sweden attacked Poland, Russia managed to gain more ground against Poland before signing a truce and instead turning its attention to Sweden and declaring war on it in 1656. The expectations of a quick defeat of Sweden and the re-conquest of Ingria proved unreal and only gave Poland the chance to recover. Peace was made with Sweden in 1658 and conflict with Poland was once again started. This stage of the campaign proved less successful for the Russians and war dragged on until 1667 and the conclusion of the Treaty of Andrusovo which recognised Russia's claims to Smolensk and Left-Bank Ukraine, including Kiev.

Rebellion of Stepan Razin

The wars with Poland and Sweden proved costly for Russia and made tax rises and conscription inevitable. This forced many peasants to escape from their masters and try their luck in the south living among the Don Cossacks. Many joined a group of Cossacks led by Cossack-turned-marauder Stepan Razin. In 1667 Razin and his motley group of Cossacks, escaped serfs and Kalmyks left the Don and sailed down the Volga intending to start a new base on the River Yaik (later renamed the River Ural). Moscow heard of these plans and ordered the governor of Tsaritsyn to stop Razin, but Razin sailed pass unhindered and set up his new base in the city of Yaitsk (now Oral in Kazakhstan). Upon being driven from Yaitsk, Razin and his men went to Azerbaijan before returning to Russia in 1669 to accept a pardon from the tsar. In 1670 Razin openly rebelled and captured Cherkassk, Tsaritsyn and then Astrakhan, where he set up a Cossack Republic. His aim was to establish the republic along the whole length of the Volga and he succeeded in capturing Saratov and Samara, but met a stumbling block in the form of Simbirsk where he was defeated by Tsarist troops and heavily injured. Razin’s promise to free the people from the rule of the boyars though has struck a chord and further uprisings had broken out in Nizhny Novgorod, Tambov, Penza and even in Novgorod and Moscow. This sentiment was further strengthened by the bloody reprisals carried out by the Tsarist regime in trying to quell the rebellions.

Razin’s campaign though had ultimately ran out of steam after Simbirsk and after the patriarch had excommunicated him. In April 1671 Razin’s campaign came to an end when he was finally captured and delivered to Moscow, where in June Razin was quartered on Moscow’s Bolotnaya Ploschad. The so-called Peasants War came to an end with Razin’s demise but reorder was only finally restored in November when Tsarist control over Astrakhan was regained.

The Schism of Russian Orthodoxy

In 1652 Metropolitan Nikon of Veliky Novgorod was elected patriarch and accepted on condition that he would be given full obedience. Nikon immediately set out revising the service books and discovered that the Russian books needed reforming to bring them in line with the Greek books. One major source of discord was the fact that it was traditional in Russia to make the sign of the cross with two fingers and not three fingers like the Greek tradition dictates. Nikon was also against the construction of churches not in the Byzantine style – St Basil’s Cathedral being a prime example of uncanonical church architecture.

The reforms were approved in 1654 in the same year as the outbreak of plague – seen as some as a bad omen of God’s displeasure at the reform. The power of the patriarch was growing to such an extent that it risked eclipsing that of the tsar. This ultimately led to his downfall in 1658 when Nikon was removed from office by the tsar. At first Nikon retired to the residence he had built in Istra, but he was later exiled to the Ferapontov Monastery outside Vologda. Despite Nikon's fall from grace, in 1666 all of his reforms were accepted by a meeting of the synod. At this time religion was a major aspect of people’s lives and many believed that even these relatively minor reforms may be wrong which would therefore endanger their souls for eternity. Those people who refused to give up their century-old traditions became known as the Old-Ritualists or Old Believers.

Persecution of the Old Believers

The so-called Old Believers who did not accept the reforms to the service books were seen as heretics and posing a danger to the authority of the Church and indeed the state itself. The protopope Avvakum strongly rejected the reforms and became the unofficial leader of the Old Believer movement. This eventually led to him being exiled to Tobolsk and then to Pustozyorsk in the far north where he was imprisoned in a dugout pit for the last 14 years of his life. In 1682 he was burned at the stake, but left behind a set of writings which is now considered a masterpiece of 17th century Russian literature.

Another significant figure of the Old Believer movement was Feodosia Morozova, sister-in-law to the boyar Boris Morozov and a rich landowner herself, which bought her into personal contact with the tsar. She was also a close associate of Protopope Avvakum, who had a great influence on her faith and she joined her mentor in rejecting the reforms. In 1671 when she refused to attend the second wedding of Tsar Alexis based on her stance regarding the reforms she was subsequently interrogated along with her sister. The two sisters were then arrested and had their property and titles confiscated. Eventually they were imprisoned in Borovsk where they died of starvation in 1675 in prison after refusing to give up their faith and accept the reforms.

Solovetsky Uprising

Nikon's reforms were also not immediately accepted at the remote fortified Solovetsky Monastery, located in the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea. The monastery's 500 or so monks rejected the reforms and Tsar Alexis was forced to send a division of the Streltsy to the island to restore order as the monastery was becoming known as a stronghold of the Old Belief and posed a risk to the implementation of the new reforms. The first Streltsy unit arrived in June 1668 and immediately began besieging the monastery. However they were only successful in suppressing the uprising in January 1676 and that was only when a traitorous monk showed the Streltsy a secret way into the monastery. The majority of the few surviving rebels were subsequently executed.

Reign of Feodor III

Tsar Alexis died in 1676 and was survived by two sets of children from his two wives: Maria Miloslavskaya who died in 1669 and Natalia Naryshkin whom he married in 1671. From his first marriage he had six surviving daughters and two sons: Fyodor and Ivan, and from his second he had a son (Pyotr) and a daughter. As the oldest surviving son Fyodor succeeded his father (as Feodor III). Feodor III was said to be highly intelligent but had been paralysed since birth after suffering from a disease. His ill health also lead to an early death aged 20 in 1682 after reigning just over six years. In his short reign he managed to oversee the foundation of the first Slavic Greek Latin Academy in Russia and reform the mestnichestvo system under which political appointments were made based on pedigree. Under the new system appointments were made on merit.

Streltsy Uprising of 1682

Upon Feodor III's death in 1682 a struggle broke out between the Miloslavsky family who wanted Ivan (the surviving son from Tsar Alexis's first marriage) crowned tsar as the legal heir, and the Naryshkin family who wanted the Pyotr (the surviving son from Tsar Alexis's second marriage) named tsar on the reasoning that he enjoyed much more robust health that the sickly and feeble-minded Ivan – he also had the support of the patriarch. To counter this, the Miloslavskys, lead by Ivan’s older sister Sofia Alekseevna, spread rumours that the Naryshkins had had Ivan murdered and uprisings broke out in Moscow lead by the Streltsy. The Streltsy stormed the Kremlin despite the fact that the Naryshkins showed the crowd Ivan to prove he was still alive.

The streltsy went on to kill several boyars including two of Pyotr’s uncles in front of the young Pyotr before a compromise was reached where Ivan would be crowned tsar (Tsar Ivan V) alongside his half brother Pyotr (Tsar Peter I – now more commonly known as Peter the Great). In addition Sofia was named regent for her mentally disabled brother and her minor half brother. Quite a coup for a woman in Russia of this age, where women were not expected to be seen. A special dual throne was built which even had a place for Sofia to sit unseen to listen and give advice to the tsars.

However the Miloslavsky clan had unwittingly unleased a monster in the form of the Streltsy as its leader Prince Ivan Khovansky – who along with the priest Nikita Pustosvyat was considered the most significant leader of the Old Believers after the death of Feodosia Morozova and Avvakum – pressed for an end to the persecution of the Old Believers. In July 1682 a debate was arranged between Patriarch Joachim and Nikita Pustovyat in the present of Regent Sofia, which broke down and turned violent. After Sofia had Nikita Pustovyat executed, the Streltsy, led by Khovansky, rebelled. Sofia and the tsars left Moscow with the court for the safety of the Troitse-Sergieva Monastery. The rebellion was eventually suppressed and the streltsy were brought under control once more after the execution of Khovansky.

Colonisation of Siberia

In the mid-17th century, the Russian colonisation of Siberia was already well under way, primarily around the rivers Tobol, Irtysh, Ob, Yenisey and Lena. The Russians reached the Sea of Okhotsk in 1639, Lake Baikal in 1643 and the Bering Straits in 1648. In 1661 Irkutsk was founded close to Lake Baikal and the city would later grow into a major centre of Siberia. In the 1640s and 1650s the Russians were coming into contact with the Chinese which led to several border conflicts. In 1689 the Treaty of Nerchinsk was signed between the Chinese and the Russians which defined the border between the two countries with Chinese keeping control of the territory to the north of the River Amur.

Young Peter the Great

While Peter’s sister was reigning in his name, Peter was content enough to spend his days in the Foreign Quarter of Moscow close to his residence in Preobrazhenskoe conversing with foreigners. While in Preobrazhenskoe Peter also created a “play army” consisting of 100 men. This play army would grow into a more professional army and in 1695 it officially became known as the Preobrazhensky and Semenovsky Regiments of the Guard.

Peter also developed a passion for all things nautical during his youth, after supposedly discovering an old boat in Moscow’s Izmailovo Estate, which some believe may have been a gift from Queen Elizabeth of England to Tsar Ivan the Terrible. In 1688 Peter founded a “play fleet” on Lake Plescheevo in Pereslavl-Zalessky and in 1692 organised a ceremonial review.

The Ascension of Peter the Great

By 1689 the regency of Sofia had become considerably weaker after two unsuccessful campaigns against Crimea. Peter had also reached majority (and even grown to over two metres in height) and now he considered it was time to rule without a regent. In 1689 Sofia once again decided to use her connections with the leaders of the Streltsy to her advantage, but this time was less successful as Peter was warned and able to escape to the Troitse-Sergieva Lavra. Sofia’s moment was over as more and more supporters shifted to Peter’s cause. When Peter returned to Moscow he had Sofia arrested and imprisoned in the Novodevichy Convent. Two of Sofia’s most powerful supporters were also removed: Fyodor Shaklovity, the leader of the Streltsy, was executed in October 1689 and Vasily Golitsyn, foreign minister and a possible lover of Sofia, was exiled to Kholmogory. In 1696 Peter’s co-ruler, his half brother Ivan V, died leaving Peter as the sole tsar – although even before this Ivan played very little role in the running of the state.

The Origins of the Russian Navy

Peter the Great wanted to turn his nation into a naval power and the first obstacle for this was the lack of access to the sea. The only sea port Russia had was that of Arkhangelsk on the White Sea so Peter set off there to establish a shipyard in 1693. However the port was limited by the fact that it was blocked by ice for five months of the year. What Peter really desired was access to the Sea of Azov and thereby the Black Sea but the Ottoman fortress of Azov stood in his way. In 1695 Peter launched the First Azov Campaign in an attempt to capture the fortress. The Russian army was able to block the fortress via land but could not stop the fortress from being supplied by sea, resulting in the failure of the siege.

After the first campaign against Azov Peter's belief of the importance a naval fleet was strengthened and so he set about to rectify this. Peter decided to establish an admiralty wharf in Voronezh to build his new fleet and shipbuilding began in 1696 - this is now considered the year of foundation of the Russian navy. Thanks to the new fleet Russia was successful in the Second Azov Campaign in the winter of 1696 and captured the fortress. In 1698 just further down the coast Peter founded a new base for his navy in Taganrog.

Grand Embassy of Peter the Great

In 1697 a group of over 50 diplomats and experts in various fields left Russia as part of a grand embassy to visit Western European countries with the aim of strengthening and widening the alliance against the Ottoman Empire, promoting the image of Russia abroad, hiring foreign experts and learning about shipbuilding and other military matters. Officially the mission was headed by three of Tsar Peter’s most trusted confidants, although Peter also accompanied the mission incognito as Pyotr Mikhailovich. The mission travelled to Saxony, Brandenburg, Holland, England, Austria and Poland. While in Holland and England, Peter not only learned about shipbuilding but actually took part in the process first hand at wharfs in Zaandam and Deptford. In England he also visited the Greenwich Observatory, the Royal Mint and Oxford University, while trashing his residence in the process during wild sessions of drinking.

Streltsy Uprising of 1698

While still in Europe news reached Peter that the Streltsy had once again risen up against his authority and Peter was forced to cut short his travels and return to Moscow. Back in March 1698 a group of dissatisfied Streltsy had made contact with Sofia Alekseevna who was still imprisoned inside Moscow’s Novodevichy Convent. Later in June a larger group of Streltsy rebelled intent on overthrowing Peter and putting his half-sister on the throne, however the full extent of Sofia’s role in this rebellion is unknown. The rebellion was unsuccessful and suppressed by Peter’s Preobrazhensky and Semyonovsky Regiments. By the time Peter returned in August investigations were underway, often involving torture. This was followed by the execution of over 1000 Streltsy, with Peter allegedly beheading some of the men himself. Over 600 others were branded and sent into exile.

The Streltsy as an entity were no more. In addition Peter took no precautions with his half-sister. She was forced to take the veil and kept under strict surveillance in the Novodevichy Convent, only being allowed to leave her cell on Easter. It is also said that the bodies of some of the executed Streltsy were hung up outside her window. Sofia died in her cell in 1704, despite her fall from grace, for a period Sofia was the most powerful woman Russia had seen since the regency of Olga in the 10th century.

Westernisation

After returning to Russia from the West, Peter was convinced that the old ways of Moscow were holding the country back. Russia needed to modernise and to do this it must adopt Western traditions, scientific advances and technology. Peter commanded that his court abandon their traditional robes in favour of western style clothing and in 1698 he introduced a beard tax to dissuade Russians from wearing long beards. In 1699 Peter also changed the traditional Russian calendar which was based on the believed number of years from the creation of the earth. Therefore the year 7207 became 1700. The date New Year was celebrated was also moved from 1st September to 1st January. Russian was on a new course heading west.